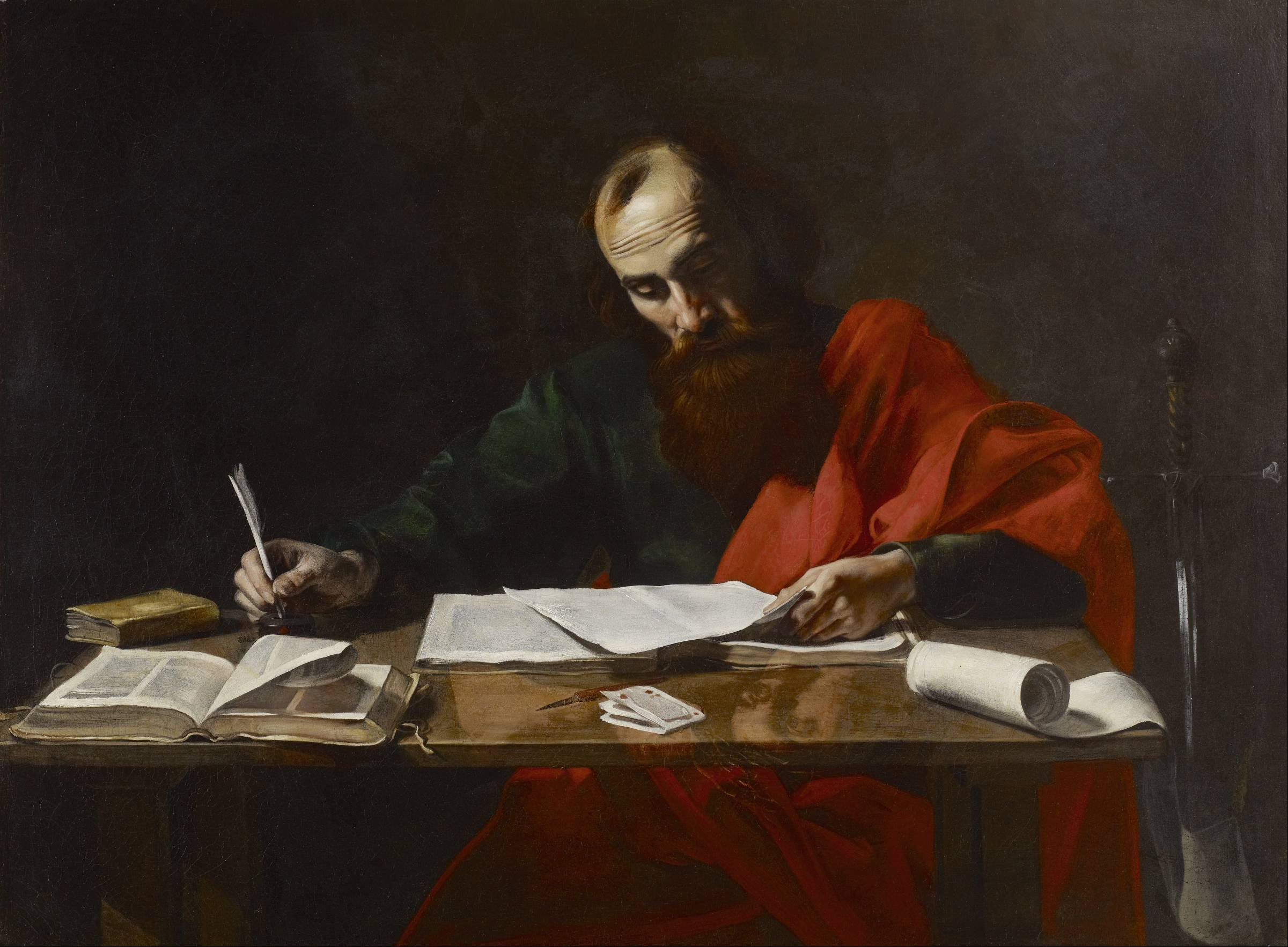

Paul, the ancient missionary and apostle, suddenly appears, alive and well in a 21st century university. After spending a few years learning and reading with his friend, Professor Don, he answers questions of students in the professor’s class.

Fred (a student of philosophy): So I was wondering about what you felt about the predictions you made as Paul the apostle.

Paul: Everything I have done since I met Jesus has been as Paul the apostle. But what predictions are you referring to?

Fred: For one, you said that when Jesus returned that the “dead in Christ would rise first” and then the church would be raptured.

Paul: Well, Jesus has not yet come to earth, and the angelic herald of the new age hasn’t appeared. So the resurrection hasn’t happened yet.

Fred: And that is what confuses me. Because you also said that after the “man of sin” came, then Jesus would return. But hasn’t the man of sin come? In 70AD?

Paul: Ah, let me make some clarification. To those of you who do not understand what my friend is speaking of, it refers to me speaking of Jesus’ predictions of the beginning of the next age.

Fred: They were not your own? Jesus never spoke of a “man of sin”.

Paul: I was using just different language for what Jesus spoke of. Jesus did speak of an “abomination of desolation”, which is referred to in Daniel. What chapters, Don?

Don: Daniel, near the end of chapter 11 and also chapter 12.

Paul: Alright. To understand what Jesus was speaking of, we have to know what Daniel was speaking of.

Fred: Do you hold that Daniel wrote the book of Daniel?

Paul: Not most of it. You note that the book was written in third person, except for a specific section written in first person. So the first person might have been written by Daniel, and the rest clearly written by someone else after the fact. Anyway, the writer—whoever he might have been—was speaking of the time of Antiochus Ephiphanes—the evil ruler of the Syrians—who established Zeus worship in the temple. He persecuted and killed the people of God, and tried to wipe out all worship of Yahweh, the God above all gods. Jesus, then was speaking of one who would do the same—halt the true worship in the temple and persecute the people of God and attempt to halt worship of Yahweh.

Fred: And the one who does this is the “man of sin”?

Paul: Yes. That’s the term my communities understood better than the Daniel reference.

Fred: Isn’t this the same as what fundamentalists call “the antichrist”?

Paul: Yes and no. The term is used as a misunderstanding of a passage in the first epistle of John—John was referring to false teachers, of which there will be one in the final part of this age as well. But certainly, like the “antichrist”, the abomination would be a powerful ruler, able to use armies to persecute all the people of God. But as far as man of sin having a collection of nations or having died and come back—Jesus didn’t speak to that.

Fred: But didn’t the book of Revelation?

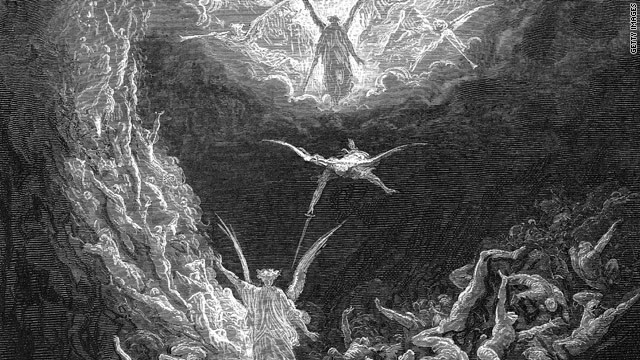

Paul: People read so much into that book. It’s fairly simple, really. It is a description of Jesus’ prophecies of the change of ages and some prophetic passages told from the perspective of heaven and the end of the first century. Much of that isn’t necessarily going to come true.

Fred: Don’t you hold to the inspiration of that prophecy?

Paul: Actually, I do. It truly seems to be a revelation from heaven. But that doesn’t mean that it will all come to pass—because of God’s mercy. It is a warning, just like Jonah’s. But Jonah’s prophecy didn’t come to pass, not because it didn’t really come from God, but because God had mercy on their repentance.

Fred: Okay, interesting. So about the man of sin or whatever we want to call him. Didn’t Jesus said that such a one would come just at the cusp of his coming to earth to rule?

Paul: Hmm. I suppose if you wanted to read it that way you could. But that isn’t really what he said. He said that the abomination would come and then “after that time” he would return and rule the earth. Jesus really prophesied two main events—his coming and the time of persecution of God’s people which ends with the destruction of the Temple. The first event comes after the second, without any description of how soon one comes after the other.

Fred: So even though the Temple was destroyed in 70AD…

Paul: That doesn’t necessarily have anything to do with Jesus’ return. Titus, who destroyed the temple, was certainly the man of sin because he defiled the temple and stopped the worship of Yahweh there.

Fred: So, you would say that there is no antichrist to come, as the fundamentalists say?

Paul: Many men of sin have come, even if they have not been able to destroy the temple for 2000 years. Every single emperor, king, pope, prime minister, chancellor, priest, pastor, rabbi, imam or parent who tries to cease the true worship of God as described and lived out by Jesus is a form of the antichrist. Anyone who uses their authority to stop the true worship of God, the Lord of the Universe, is an abomination. There has never been an age or a community without them—they always exist. So to have a worldwide persecution of God’s people? I would not be surprised if it does not come again and it would trigger Jesus’ return, just as the book of Revelation stated.

Fred: Does it bother you that you and Jesus prophesied his return and after 2000 years it hasn’t happened? Doesn’t it cause you to doubt that He would come at all?

Paul: Honestly, at first, it did truly disturb me. When I first arrived here in this place, I was wondering if I had actually arrived in the midst of Jesus’ rule. I quickly found out that wasn’t true. And so I wondered if I was right—if perhaps Jesus wouldn’t return. But in looking over the history of the last two thousand years, I think I understand why he has not come back.

Fred: (Sarcastically) Oh, do tell.

Paul: (Sincerely, not picking up on Fred’s tone) Thank you. There were a few conditions for Jesus to return. First, there had to be a prepared people of God ready to rule for God. This is what the ministries of John the Baptist and Jesus were all about—to prepare a people of God ready for God’s transfer of the earth to His rule. If there isn’t a people ready, then those who claim to be God’s people will be judged. So the first thing I must say is that the church has never been ready for Jesus’ return. Too often the church finds themselves on the side of the persecutors, instead of the persecuted, the oppressors instead of the oppressed.

Fred: So the church needs to be purified?

Paul: Purified? Well, not exactly. But there must be a group that is ready to rule. This means that they have their own alternative economy—one based on charity—their own alternative rule, based on mercy and repentance, their own alternative law, based on the law of Jesus, their own alternative way of obtaining power, through humility instead of gathering a power base. They must be separate from the world, and too often the church has played this dance of compromise with the world, going for quantity of disciples, rather than discipleship in Jesus. Jesus will never return if the church doesn’t reflect His way of ruling.

Fred: So why else would Jesus not return?

Paul: Because the world just isn’t evil enough. For instance, there hasn’t been a focused persecution of all the church. No one—yet—has tried to stop all the worship of Yahweh and to destroy all those who are devoted to Him. There have been pockets of persecution, but no one yet has tried to wipe out the existence of those who worship God. Also, the world has actually improved their assistance of the poor, even if they haven’t welcomed them as equal citizens.

Fred: Wait, the poor can vote in the U.S….

Paul: But they are treated as less than real citizens—whether immigrants, illegal immigrants, the homeless, the mentally ill—they are all treated as people who need to be taken care of, but can’t make decisions for themselves, or are treated as a lower class. But that doesn’t take away my point that they are assisted better than at any time in history. Jesus’ teaching accomplished that in part, but I am impressed. I am sure that Jesus is, as well. And so he wouldn’t destroy the earth as long as they are helping the poor.

Fred: So, do you think that Jesus will just put off his return indefinitely?

Paul: Honestly, I doubt it. There will come a time when the selfishness of humanity will win out. Perhaps it will be capitalism, perhaps it will be a new government, perhaps it will be a world-wide religion or anti-religion. But something will happen which will make the worship of God through Jesus unacceptable. That’s the way it always was, even in the church. And it will happen again, and the universities and governments and police departments will look at a relatively small group of true believers in Jesus and say that they have to go. When that happens Jesus will return and take control for those who call on his name.

Fred (a student of philosophy): So I was wondering about what you felt about the predictions you made as Paul the apostle.

Paul: Everything I have done since I met Jesus has been as Paul the apostle. But what predictions are you referring to?

Fred: For one, you said that when Jesus returned that the “dead in Christ would rise first” and then the church would be raptured.

Paul: Well, Jesus has not yet come to earth, and the angelic herald of the new age hasn’t appeared. So the resurrection hasn’t happened yet.

Fred: And that is what confuses me. Because you also said that after the “man of sin” came, then Jesus would return. But hasn’t the man of sin come? In 70AD?

Paul: Ah, let me make some clarification. To those of you who do not understand what my friend is speaking of, it refers to me speaking of Jesus’ predictions of the beginning of the next age.

Fred: They were not your own? Jesus never spoke of a “man of sin”.

Paul: I was using just different language for what Jesus spoke of. Jesus did speak of an “abomination of desolation”, which is referred to in Daniel. What chapters, Don?

Don: Daniel, near the end of chapter 11 and also chapter 12.

Paul: Alright. To understand what Jesus was speaking of, we have to know what Daniel was speaking of.

Fred: Do you hold that Daniel wrote the book of Daniel?

Paul: Not most of it. You note that the book was written in third person, except for a specific section written in first person. So the first person might have been written by Daniel, and the rest clearly written by someone else after the fact. Anyway, the writer—whoever he might have been—was speaking of the time of Antiochus Ephiphanes—the evil ruler of the Syrians—who established Zeus worship in the temple. He persecuted and killed the people of God, and tried to wipe out all worship of Yahweh, the God above all gods. Jesus, then was speaking of one who would do the same—halt the true worship in the temple and persecute the people of God and attempt to halt worship of Yahweh.

Fred: And the one who does this is the “man of sin”?

Paul: Yes. That’s the term my communities understood better than the Daniel reference.

Fred: Isn’t this the same as what fundamentalists call “the antichrist”?

Paul: Yes and no. The term is used as a misunderstanding of a passage in the first epistle of John—John was referring to false teachers, of which there will be one in the final part of this age as well. But certainly, like the “antichrist”, the abomination would be a powerful ruler, able to use armies to persecute all the people of God. But as far as man of sin having a collection of nations or having died and come back—Jesus didn’t speak to that.

Fred: But didn’t the book of Revelation?

Paul: People read so much into that book. It’s fairly simple, really. It is a description of Jesus’ prophecies of the change of ages and some prophetic passages told from the perspective of heaven and the end of the first century. Much of that isn’t necessarily going to come true.

Fred: Don’t you hold to the inspiration of that prophecy?

Paul: Actually, I do. It truly seems to be a revelation from heaven. But that doesn’t mean that it will all come to pass—because of God’s mercy. It is a warning, just like Jonah’s. But Jonah’s prophecy didn’t come to pass, not because it didn’t really come from God, but because God had mercy on their repentance.

Fred: Okay, interesting. So about the man of sin or whatever we want to call him. Didn’t Jesus said that such a one would come just at the cusp of his coming to earth to rule?

Paul: Hmm. I suppose if you wanted to read it that way you could. But that isn’t really what he said. He said that the abomination would come and then “after that time” he would return and rule the earth. Jesus really prophesied two main events—his coming and the time of persecution of God’s people which ends with the destruction of the Temple. The first event comes after the second, without any description of how soon one comes after the other.

Fred: So even though the Temple was destroyed in 70AD…

Paul: That doesn’t necessarily have anything to do with Jesus’ return. Titus, who destroyed the temple, was certainly the man of sin because he defiled the temple and stopped the worship of Yahweh there.

Fred: So, you would say that there is no antichrist to come, as the fundamentalists say?

Paul: Many men of sin have come, even if they have not been able to destroy the temple for 2000 years. Every single emperor, king, pope, prime minister, chancellor, priest, pastor, rabbi, imam or parent who tries to cease the true worship of God as described and lived out by Jesus is a form of the antichrist. Anyone who uses their authority to stop the true worship of God, the Lord of the Universe, is an abomination. There has never been an age or a community without them—they always exist. So to have a worldwide persecution of God’s people? I would not be surprised if it does not come again and it would trigger Jesus’ return, just as the book of Revelation stated.

Fred: Does it bother you that you and Jesus prophesied his return and after 2000 years it hasn’t happened? Doesn’t it cause you to doubt that He would come at all?

Paul: Honestly, at first, it did truly disturb me. When I first arrived here in this place, I was wondering if I had actually arrived in the midst of Jesus’ rule. I quickly found out that wasn’t true. And so I wondered if I was right—if perhaps Jesus wouldn’t return. But in looking over the history of the last two thousand years, I think I understand why he has not come back.

Fred: (Sarcastically) Oh, do tell.

Paul: (Sincerely, not picking up on Fred’s tone) Thank you. There were a few conditions for Jesus to return. First, there had to be a prepared people of God ready to rule for God. This is what the ministries of John the Baptist and Jesus were all about—to prepare a people of God ready for God’s transfer of the earth to His rule. If there isn’t a people ready, then those who claim to be God’s people will be judged. So the first thing I must say is that the church has never been ready for Jesus’ return. Too often the church finds themselves on the side of the persecutors, instead of the persecuted, the oppressors instead of the oppressed.

Fred: So the church needs to be purified?

Paul: Purified? Well, not exactly. But there must be a group that is ready to rule. This means that they have their own alternative economy—one based on charity—their own alternative rule, based on mercy and repentance, their own alternative law, based on the law of Jesus, their own alternative way of obtaining power, through humility instead of gathering a power base. They must be separate from the world, and too often the church has played this dance of compromise with the world, going for quantity of disciples, rather than discipleship in Jesus. Jesus will never return if the church doesn’t reflect His way of ruling.

Fred: So why else would Jesus not return?

Paul: Because the world just isn’t evil enough. For instance, there hasn’t been a focused persecution of all the church. No one—yet—has tried to stop all the worship of Yahweh and to destroy all those who are devoted to Him. There have been pockets of persecution, but no one yet has tried to wipe out the existence of those who worship God. Also, the world has actually improved their assistance of the poor, even if they haven’t welcomed them as equal citizens.

Fred: Wait, the poor can vote in the U.S….

Paul: But they are treated as less than real citizens—whether immigrants, illegal immigrants, the homeless, the mentally ill—they are all treated as people who need to be taken care of, but can’t make decisions for themselves, or are treated as a lower class. But that doesn’t take away my point that they are assisted better than at any time in history. Jesus’ teaching accomplished that in part, but I am impressed. I am sure that Jesus is, as well. And so he wouldn’t destroy the earth as long as they are helping the poor.

Fred: So, do you think that Jesus will just put off his return indefinitely?

Paul: Honestly, I doubt it. There will come a time when the selfishness of humanity will win out. Perhaps it will be capitalism, perhaps it will be a new government, perhaps it will be a world-wide religion or anti-religion. But something will happen which will make the worship of God through Jesus unacceptable. That’s the way it always was, even in the church. And it will happen again, and the universities and governments and police departments will look at a relatively small group of true believers in Jesus and say that they have to go. When that happens Jesus will return and take control for those who call on his name.